Introduction: The Starting Point of a Top Expert's Mindset

In the vast world of electronics manufacturing, electronic assembly is often seen as a relatively isolated process—a physical task of "putting parts together." However, this view is one-sided; it only scratches the surface. For the top 0.1% of experts in the industry, the true meaning of electronic assembly extends far beyond this. They view it as the "ultimate validation" of a complex system, a comprehensive challenge that spans the entire product lifecycle, integrating design, supply chain, and quality management. The real assembly process doesn't begin on the production line; it starts silently from the very first second of product design. > IPC Design Standards

This fundamental shift in mindset is about moving from a reactive to a proactive mode. Novices and junior engineers tend to adopt a reactive approach, which is to "fix problems after they occur." They rely on back-end quality control measures like Automated Optical Inspection (AOI) or manual visual inspection to find and correct defects in the product. However, this model hides enormous risks and costs. A design flaw discovered at the manufacturing stage can be 10 times more expensive to fix than if it were addressed during the design phase. If the issue isn't caught until the product is in the customer's hands, it can lead to massive recalls, warranty claims, and incalculable damage to brand reputation, with costs increasing exponentially. Therefore, a reactive mindset is a high-risk, low-efficiency mode of operation.

In contrast, top experts firmly believe that "quality is designed in, not inspected in." They adopt a proactive approach, anticipating and mitigating potential risks early in the product development lifecycle. The core of this method is to push quality control upstream, integrating considerations for manufacturing, assembly, and testing into the initial design. Industry standards like IPC-J-STD-001 & IPC-A-610 Standard further support this proactive approach, ensuring that design and manufacturing processes align with globally recognized quality benchmarks. This paradigm shift is not just a technical refinement but a strategic business imperative. It fundamentally improves product yield, reduces costs, and shortens time-to-market.

Table of Content:

- Part I: A Paradigm Shift: From Assembly to Design-Centric Thinking

- Part II: The Invisible Battlefield of Supply Chain: Evolving from Procurement to Risk Management

- Part III: The Phoenix of the Production Line: Evolving from Inspection to Quality Control

- Part IV: Insights into the Future: The Ultimate Wisdom of a Top Expert

Part I: A Paradigm Shift: From Assembly to Design-Centric Thinking

1.2 The First Principle: The Strategic Blueprint of Design for Excellence (DfX)

For a top expert, electronic assembly begins with a systematic design philosophy called Design for Excellence (DfX). DfX is not a simple set of technical rules but a comprehensive strategic blueprint. It requires designers to engage in early and continuous collaboration with manufacturing, supply chain, and other relevant teams from the very beginning of product development. This "Shift-Left" approach enables the identification and resolution of potential issues in the design phase, thereby avoiding expensive design iterations and rework.

The core of DfX includes a series of sub-concepts, with the most fundamental and crucial being Design for Manufacturing (DFM) and Design for Assembly (DFA).

- The core principles of DFM are aimed at simplifying the manufacturing process, reducing production costs, and improving yield. This includes:

- Simplifying product design: Reducing the number of parts, integrating multiple functions into a single component, or redesigning the enclosure to reduce assembly steps.

- Standardizing components: Prioritizing the use of readily available, common, and cost-effective "off-the-shelf" components. This not only lowers costs but also simplifies complex inventory management. >Component Sourcing from NextPCB HQOnline

- Considering manufacturing tolerances: Setting achievable tolerances in the design, avoiding unnecessarily tight tolerances. Overly strict tolerances can significantly increase manufacturing difficulty and cost without providing a proportional functional benefit.

- The core principles of DFA focus on the convenience and efficiency of assembly. The goal is to reduce the number of assembly steps and their difficulty. For example, engineers might design symmetrical parts to prevent incorrect orientation or use self-aligning features to simplify component placement. You can also request a free DFM/DFA check early.

In practice, a mindset seemingly contrary to industrial DFM is worth exploring: the amateur or "maker" mentality. These communities often prefer through-hole components and avoid direct mounting of peripherals for ease of manual debugging and repair. Their goal is the serviceability of a single product, which appears to conflict with industrial DFM's pursuit of high-density, integrated surface mount devices (SMD) and high packaging density. However, from a deeper perspective, the goals of these two methods are not in opposition but are optimized for different product lifecycles and scales. The hobbyist's goal is the repairability of a single unit, while the goal of industrial DFM is to achieve high reliability, low cost, and a long lifecycle under mass production. The high reliability achieved through DFM/DFA fundamentally reduces the need for repair. Therefore, neither mindset is inherently superior; they are simply the best response to different application scenarios and market demands.

To more clearly illustrate the fundamental differences between these two mindsets, Table 1.1 provides a detailed comparison of novice and expert approaches to key electronic assembly decisions.

Table 1.1: A Comparison of Novice and Expert Decision-Making in Electronic Assembly

|

Decision Area |

Novice Approach |

Expert Approach |

|

Design Philosophy |

Focuses solely on functional implementation, viewing manufacturing as a downstream problem. |

Adopts a DfX framework, integrating manufacturability and assembly into the initial design. |

|

Supply Chain Management |

Focuses only on the unit price and immediate availability of components. |

Evaluates Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) and builds a resilient supply chain. |

|

Production Collaboration |

Sends design files to the factory only after completion, relying on the factory for DFM checks. |

Collaborates with the manufacturing team early in the design phase, performing "Shift-Left" analysis. |

|

Quality Control |

Relies on end-of-line inspection to find and correct problems. |

Utilizes a data-driven, automated quality control loop to eliminate defects at the source. |

Part II: The Invisible Battlefield of Supply Chain: Evolving from Procurement to Risk Management

2.1 Beyond Unit Price: A Deep Dive into Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)

In the supply chain management of electronics manufacturing, one of the most common and fatal pitfalls is focusing solely on the unit price of a component. This shortsighted procurement model often leads decision-makers into the "lowest unit price" trap. Top experts know that the true cost is hidden throughout the product's entire lifecycle. Therefore, they use a Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) framework to evaluate all direct and indirect costs.

TCO is like a vast iceberg, with the unit price being just the tip that's visible above the water. Below the surface lies a huge and complex array of hidden costs, including:

-

Acquisition and Logistics Costs: In addition to the cost of the components themselves, one must consider shipping fees, customs duties, and storage costs. Some suppliers, to lower the unit price, require large-volume orders, which leads to high inventory costs.

-

Operational Costs: These are the ongoing expenses incurred during production and testing, such as engineering support, design validation, electrical and mechanical testing, and the costs of compliance documentation and certifications.

-

Quality and Risk Costs: This is the most easily overlooked yet most impactful category. If you choose a supplier with unstable quality, you may later face high costs for rework, repairs, product recalls, and warranty claims due to batch defects.

-

End-of-Life Costs: These costs are related to a product's disposal and management, such as the redesign required due to component obsolescence, as well as the costs of e-waste disposal and recycling.

On the surface, choosing the lowest-bidding supplier seems to save money. However, this choice often comes with a higher TCO. For example, a low-priced supplier might have poor quality control, leading to rework and recall costs from batch defects that far exceed the initial savings. Furthermore, large-volume orders from a supplier can increase inventory risk, potentially leading to components becoming obsolete before they are even used in production. Therefore, the TCO framework forces decision-makers to shift from short-term price considerations to long-term systemic risk management, leading to more strategically valuable decisions.

Table 2.1: A Dissection of Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) Components

|

Cost Category |

Detailed Items |

|

Acquisition Costs |

Unit component price, assembly and labor costs, tooling/fixture fees, inbound freight |

|

Operational Costs |

Engineering support and validation, electrical and mechanical testing, compliance certification fees, quality assurance processes |

|

Supply Chain Costs |

Shipping and tariffs, lead time variability, inventory storage and management fees |

|

Quality and Warranty Costs |

Product rework and recalls, warranty claims, customer dissatisfaction, compliance failure remediation |

|

End-of-Life Costs |

Component obsolescence management, waste disposal, salvage and recycling costs |

2.2 Building Resilience: The Art of Multi-Sourcing and the Living BOM

In a globalized and highly interconnected supply chain, tying success to a single external relationship is a huge risk. Geopolitical instability, natural disasters, or even operational issues within a single supplier can lead to production interruptions. To counter this uncertainty, top companies have long abandoned the traditional single-sourcing model in favor of a multi-sourcing strategy. This approach disperses risk by procuring the same components from multiple suppliers, providing an extra layer of flexibility and a safety net to avoid production bottlenecks caused by issues with any one vendor.

To effectively manage the complexity introduced by multi-sourcing, relying on a static Bill of Materials (BOM) is insufficient. A traditional BOM is a static document that simply lists the required parts and quantities. However, top companies today use real-time, dynamic BOMs, which are tools that can synchronize in real time with global supply chain databases, upgrading the BOM from a simple list to an intelligent risk management hub.

The core functions of a dynamic BOM include:

- Real-Time Risk Assessment: Continuously monitoring the availability, price, lead time, and lifecycle status of every component in the BOM.

- Predictive Insights: Using historical market data and real-time analytics to forecast potential component shortages or price fluctuations.

- Intelligent Alternatives: Automatically identifying high-risk or out-of-stock components and recommending compatible Form, Fit, and Function (FFF) alternatives.

This dynamic BOM is a concrete embodiment of the proactive mindset in supply chain management. The traditional approach is to passively wait for a supply chain problem to occur—for example, discovering a critical component is out of stock the day before production, then scrambling for a solution, leading to production halts and delivery delays. The dynamic BOM, in contrast, turns this reactive response into proactive prevention. Through real-time data streams, it sends alerts before a problem arises and offers solutions, transforming risk from an "unforeseen disaster" into a "manageable variable."

Table 2.2 compares the pros and cons of these two procurement strategies to help decision-makers weigh their options.

Table 2.2: A Comparison of Single-Sourcing vs. Multi-Sourcing

|

Sourcing Strategy |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Single-Sourcing |

Simplified relationship, easier to build long-term partnership, may achieve bulk pricing advantages. |

High-risk concentration, dependent on a single supplier, massive impact in case of disruption. |

|

Multi-Sourcing |

Risk dispersion, enhanced supply chain resilience, avoids production bottlenecks. |

Increased management complexity, more communication channels, may lose some bulk discounts. |

Part III: The Phoenix of the Production Line: Evolving from Inspection to Quality Control

3.1 The Essence and Challenges of the Physical Process

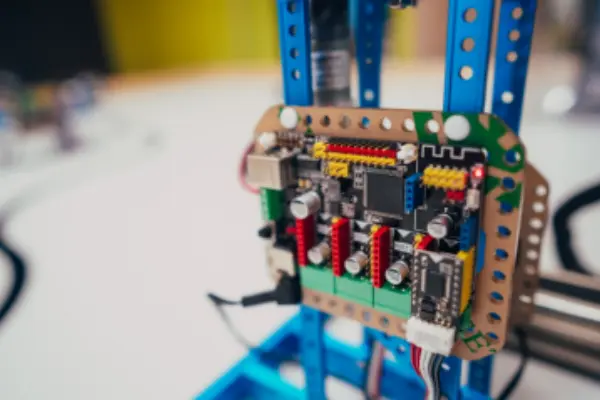

The core of modern electronic assembly is Surface Mount Technology (SMT). It is a precise and highly automated process with the following main steps:

-

Solder Paste Printing: A high-precision stencil is used to apply solder paste precisely onto the pads of the PCB. Solder paste is a mixture of tiny solder balls and flux, providing the foundation for subsequent soldering.

-

Component Placement: High-speed pick-and-place machines, guided by software, place tiny surface mount devices (SMD) onto the solder-pasted pads with extreme precision and speed.

-

Reflow Soldering: The PCB with components is passed through a reflow oven. The oven's pre-configured temperature profile melts the solder paste at a specific time, allowing it to solidify and form strong mechanical and electrical connections, firmly bonding the components to the board.

In addition to SMT, some large, high-power, or high-mechanical-strength components (such as connectors, electrolytic capacitors, etc.) still require Through-Hole Technology. These components are inserted into pre-drilled holes in the PCB and are soldered using Wave Soldering or selective soldering to ensure a reliable connection. During wave soldering, the PCB passes through a wave of molten solder, which completes the soldering of all through-hole components.

> Recommend reading: Reflow Soldering vs Wave Soldering

3.2 The Data-Driven Quality Control Loop: From Detection to Continuous Improvement

After the physical assembly process, the traditional approach is to perform manual visual inspection or use automated equipment to find defective products. However, quality control in top production lines has moved beyond simple defect screening and into a data-driven continuous improvement phase. They view automated inspection tools, such as Automated Optical Inspection (AOI) and X-ray Inspection, as a means of data collection, not just as defect finders.

- AOI uses high-resolution cameras and intelligent algorithms to scan the circuit board from multiple angles and under various lighting conditions. It can accurately detect surface defects like solder paste printing, component placement, and solder joint quality, including missing components, incorrect parts, and polarity errors.

- X-ray inspection has a "see-through" capability, allowing it to inspect solder joints that are not visible through optical means, such as the hidden solder balls under Ball Grid Array (BGA) packages, and to find internal defects like voids or bridges.

> Recommend reading: 13 Popular PCB Test Methods in PCB Manufacturing

The true value of these inspection tools lies in their ability to generate a vast amount of real-time data on production defects. The novice's mindset is to use this data to find bad products and then rework or scrap them. In contrast, top experts use this defect data as valuable feedback for Root Cause Analysis and parameter optimization upstream. They analyze the data to identify recurring patterns, such as placement deviations for a specific component or unstable solder paste volume in a certain area. They then feed this analysis back to the upstream solder paste printer or pick-and-place machine to adjust parameters in real-time, thereby solving the problem at its source and preventing the same defects from recurring in subsequent production batches.

This "data-analysis-feedback-optimization" closed-loop system transforms the production line from a place of "defect creation and screening" into an intelligent system of "continuous learning and optimization." This is the ultimate expression of the proactive mindset on the production floor, fundamentally improving yield and reducing the costs of rework and scrap.

Table 3.1: The Value Flywheel of Automated Quality Control

|

Step |

Detailed Description |

|

1. Automated Detection |

Utilizes AOI and X-ray equipment for high-precision, non-contact scanning of each PCB to identify all physical defects. |

|

2. Data Collection and Analysis |

The system automatically records all defect data, including defect type, location, and frequency, for aggregated analysis. |

|

3. Root Cause Feedback |

Engineers use the analysis results to identify the root cause of the defects, such as equipment calibration drift, improper process parameters, or component batch issues. |

|

4. Process Optimization |

Based on root cause analysis, real-time adjustments are made to upstream production parameters, such as solder paste thickness and stencil design, placement programs, or reflow oven temperature profiles. |

|

5. Increased Yield |

Defects are eliminated at the source, and the production process is continuously optimized, thereby significantly improving the pass rate. |

3.3 Traceability: Paving the Way for Compliance, Recalls, and Optimization

In the complex global electronics supply chain, relying solely on end-of-line quality control is not enough. Top experts also establish a robust traceability system to manage potential risks and challenges. Traceability is the ability to track a product or any of its constituent parts throughout its entire journey, from procurement and production to final delivery, ensuring that a clear record is maintained for all stages.

The key to implementing traceability is to assign a unique barcode or QR/laser mark to every component reel, every PCB, and even every final product. These unique physical identifiers establish a permanent link with digitized production data (such as batch numbers, supplier information, production dates, and test results).

The strategic value of traceability is reflected in the following aspects:

- Risk Mitigation and Precise Recalls: If a core component batch is found to be defective, the traceability system can quickly locate all PCBs that used components from that batch, enabling precise recalls that minimize losses and damage to brand reputation.

- Quality Improvement: Traceability data can be analyzed to determine if the failure rate of a specific product batch is linked to a particular supplier or production lot, providing solid data support for supplier audits and continuous improvement.

- Regulatory Compliance: In highly regulated industries such as medical, automotive, and aerospace, traceability is mandatory and is a cornerstone for meeting industry standards and earning customer trust.

Part IV: Insights into the Future: The Ultimate Wisdom of a Top Expert

4.1 Systems Thinking: The Path of a Senior Engineer's Growth

In today's fast-changing electronics industry, a top expert is no longer just a screwdriver expert who masters a single technology. They are a systems-level thinker who can integrate multiple disciplines, including electronic engineering, mechanical design, supply chain management, financial analysis, and project management. Their core competence is not in solving single, isolated problems but in understanding the interconnections and systemic impacts of problems.

The core capabilities of this strategic thinking include:

-

Questioning the Status Quo: Constantly asking strategic questions like "why" and "how can we do better," challenging traditional notions, and inspiring innovative solutions.

-

Embracing Collaboration: Recognizing the importance of cross-departmental collaboration and proactively communicating with all stakeholders, including design, manufacturing, procurement, and sales teams.

-

Data Insight: Extracting trends and patterns from a vast amount of data, not just listing numbers. They can use data to predict risks, optimize processes, and make informed decisions.

-

Adaptability: Being flexible in the face of ever-changing technology and markets, not adhering to a rigid roadmap, thereby maintaining a competitive advantage for the enterprise.

4.2 Conclusion: To the Innovators of the Future

The true art of electronic assembly does not lie in a flawless solder joint but in the vast strategic web woven from DfX, TCO, a resilient supply chain, and data-driven quality control. This is a comprehensive game that transcends the physical level.

It is my hope that this article will help future engineers and innovators break through a narrow technical perspective. When you approach the topic of electronic assembly, you will no longer see it as a simple set of operational steps but as a complex and precise ecosystem built on design philosophy, supply chain resilience, and intelligent quality control.

When you hold a PCB in your hands, you will not only see dense pads and components but a future product shaped by strategic decisions, an elastic supply chain, and intelligent quality assurance. The journey to becoming a top expert is precisely the process of growing from a reactive executor into a systems-level innovator who can proactively shape the future.

> Recommend reading: PCB Manufacturing Basics: Design, Fabrication, Testing, and Compliance

Get started now

Begin with a free DFM/DFA check and get an instant PCBA quote to turn your design-centric strategy into real, shippable hardware.