Introduction

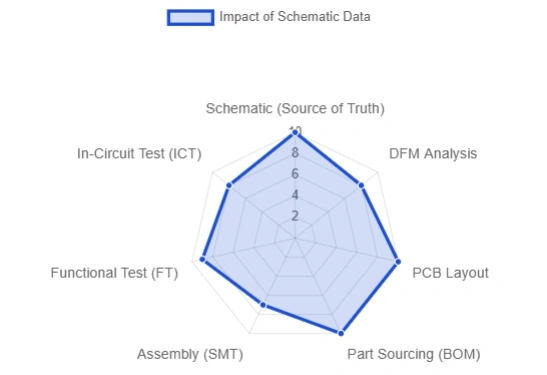

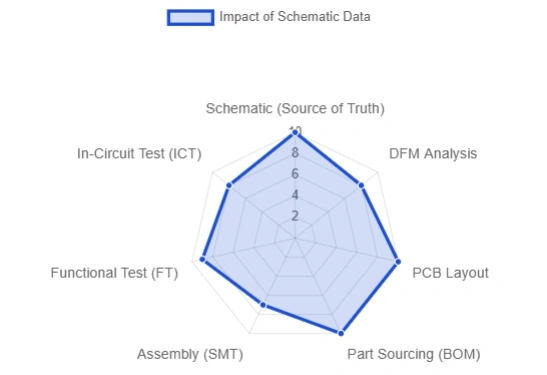

The schematic diagram is the logical representation of an electronic system's function, distinct from wiring or layout diagrams. It defines the electrical connectivity between components and serves as the core source for PCB layout and manufacturing deliverables.

Key takeaways: 1) A schematic only expresses functional logic, clearly distinguishing it from the physically focused Wiring Diagram and PCB Layout. 2) Adherence to IEC/IEEE international standards and consistent Reference Designators (RefDes) is fundamental for unambiguous collaboration and manufacturing. 3) A rigorous drafting process must include Electrical Rules Check (ERC) and Netlist generation to ensure data precision, directly impacting Design for Manufacturing (DFM) and In-Circuit Testing (ICT).

Reader Benefits: Readers will learn how to embed DFM constraints using schematic tools (ERC/Net Class), master an actionable design and verification workflow, and access a comprehensive design checklist.

Contents

- 1. What Is a Schematic Diagram?

- 2. Schematic vs. Wiring vs. Layout vs. Block

- 3. Standards & Notation

- 4. Reading a Schematic (Reading Methods)

- 5. How to Create a Schematic (Practical Workflow)

- 6. Best Practices Checklist

- 7. Common Mistakes (High-Frequency Errors)

- 8. From Schematic to Manufacturing (Production Realization)

- 9. FAQ

- 10. Glossary (Quick Reference)

1. What Is a Schematic Diagram?

1.1 Plain-language Definition

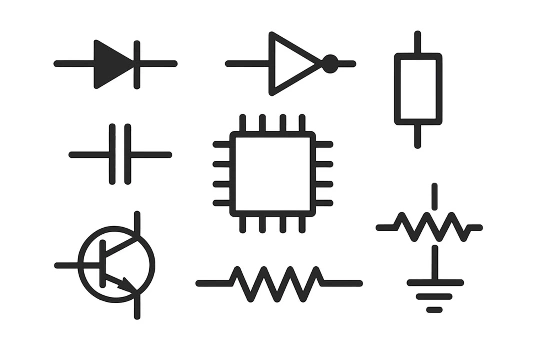

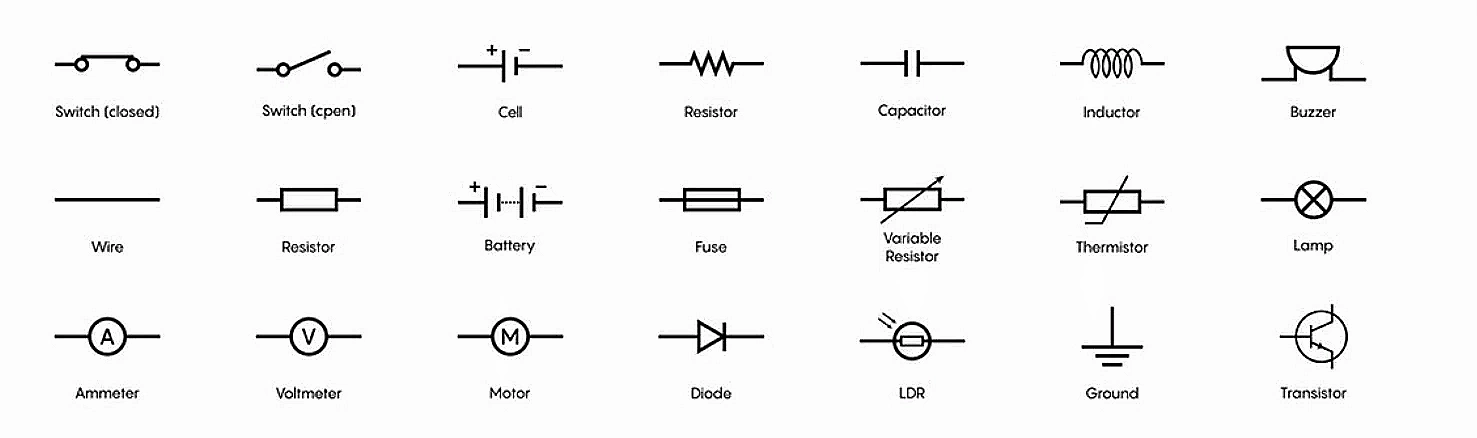

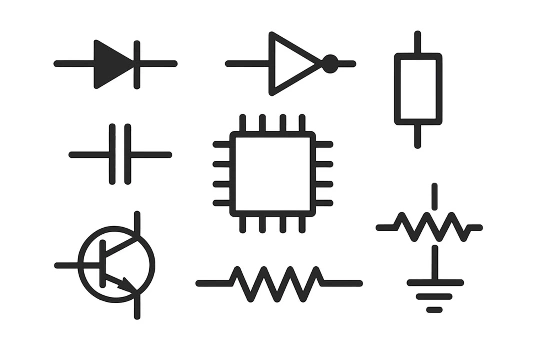

The Schematic Diagram, or circuit diagram, is the logical blueprint of an electronic system as a functional entity. It is a highly abstract and symbolic representation that uses standardized graphic symbols for physical components (such as resistors, ICs, and transistors) and lines to represent the electrical connection paths between them.

The core principle of a schematic is to convey functional connectivity—which pin connects to which pin—without regard for the actual physical arrangement of these components in the final device. This abstraction allows engineers to easily understand and analyze the circuit's function without being distracted by physical layout constraints.

A schematic is fundamentally composed of three elements:

- Components: Represented by standard symbols, labeled with a Reference Designator (RefDes) and a value.

- Connection Lines: Representing electrical nets (Net).

- Net Name/Label: Used to assign a unique identity to an electrical connection, which is crucial for cross-page or distributed nets.

While a schematic is known for its abstraction and omission of irrelevant details, when created for manufacturing or simulation, a balance must be maintained between functional clarity and necessary physical details. For modern ECAD (Electronic Computer-Aided Design) tools, the component symbol must include all physical pins on the device; even unconnected or reserved pins (NC pins) need to be clearly marked. Omitting these physical details in the schematic symbol can cause errors or failures during subsequent netlist generation and footprint mapping. Therefore, a schematic created for manufacturing must faithfully reflect the component's full physical interface information while maintaining logical clarity.

1.2 What a Schematic Is Not

A common mistake for novice designers is confusing the logical schematic with documentation that reflects physical location. Defining the boundaries of the schematic is critical:

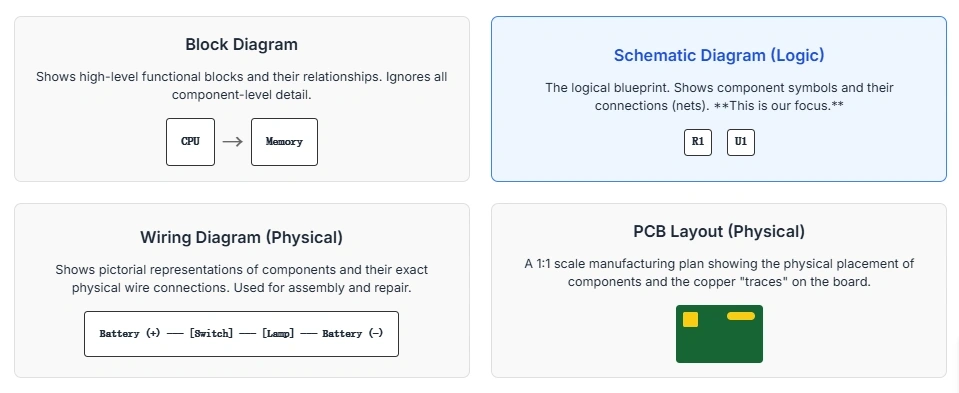

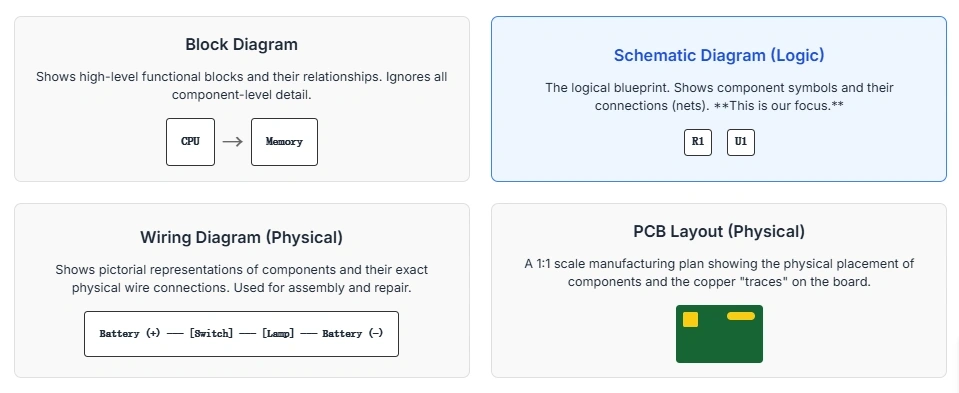

- Not a Wiring Diagram: A Wiring Diagram is intended to provide the physical point-to-point routing or cable paths required for assembly or maintenance. Wiring Diagrams focus on physical implementation and assembly instructions; Schematics focus on circuit function and logical connection.

- Not a PCB Layout/Artwork: The arrangement of schematic symbols on the drawing sheet bears no necessary relationship to the actual physical position of the corresponding components on the Printed Circuit Board (PCB Layout). The PCB Layout is the physical implementation file (e.g., Gerber files), driven by the Netlist generated from the schematic.

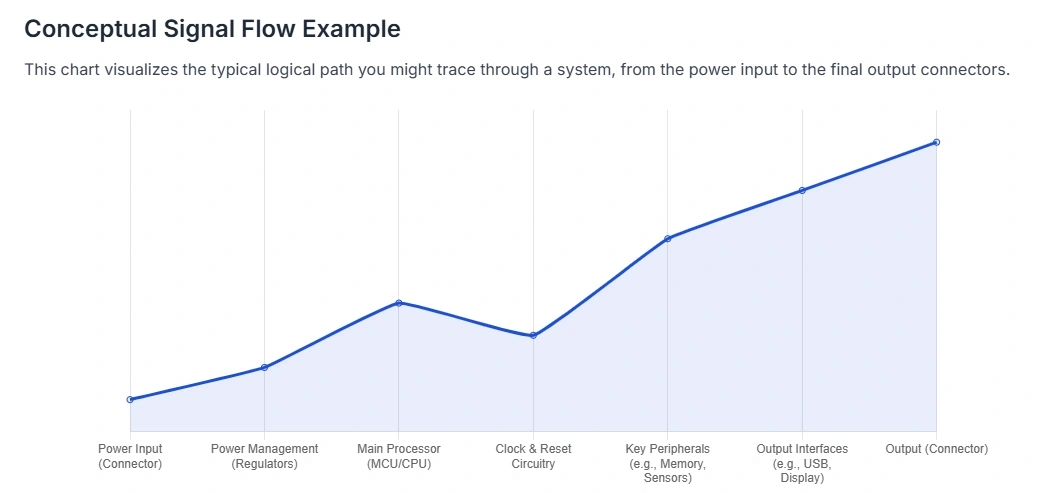

- Not a Block Diagram: A Block Diagram shows the high-level organizational structure of functional units (e.g., "Power Management," "Microcontroller," "RF Module"). It omits specific component-level connection details. The schematic provides the finer-grained electrical connections both within and between these functional blocks.

2. Schematic vs. Wiring vs. Layout vs. Block

Understanding the distinctions between various electronic diagrams is fundamental for effective hardware team communication, ensuring the correct documentation is used for different tasks such as debugging, assembly, or manufacturing.

> Recommend reading: PCB Schematic vs PCB Layout

2.1 Comparison Table

The table below details the distinct roles played by each major drawing type throughout the product lifecycle.

Table 1: Comparison of Electronic Diagrams

| Diagram Type |

Purpose |

Reflects Physical Location |

Primary Output/File |

Primary Audience |

Typical Use Case |

| Schematic Diagram |

Defines logical electrical connectivity and function. |

No (optimized for functional clarity and signal flow). |

Netlist, Bill of Materials (BOM) |

Electrical Engineer, Circuit Debugging, Layout Input |

Design creation, simulation, code review |

| Block Diagram |

Shows the organizational relationship between functional units. |

High-level organizational structure only. |

System Architecture Document |

System Architect, Project Manager |

Project planning, high-level functional overview |

| Wiring Diagram |

Illustrates physical point-to-point connections needed for assembly or maintenance. |

Yes (focuses on physical routing of cables/harnesses). |

Assembly instructions |

Wiring/Assembly Technician |

Harness assembly, field service/repair |

| PCB Layout |

Defines the precise physical placement of components and copper routing on the board. |

Yes (exact component location and trace paths). |

Gerber Files, ODB++ |

PCB Manufacturer, Layout Engineer |

Manufacturing and Assembly (SMT/THA) |

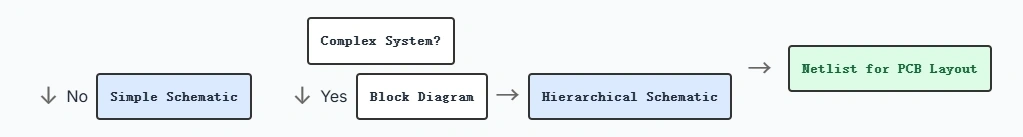

2.2 When to Start with a Block Diagram, When to Draw a Schematic Directly

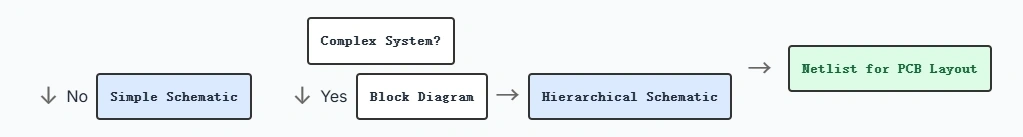

System complexity is the determining factor for the starting point and structure of the design:

- Flat Design (Direct Schematic): For simple circuits (e.g., single-stage amplifiers, small regulators), where component count is low, a single-page or "flat" schematic structure can be used, drawing connections directly.

- Hierarchical Design (Start with Block Diagram): For complex systems (e.g., embedded Linux modules, multi-channel RF systems), starting with a Block Diagram is crucial. The Block Diagram logically partitions the design, defining major communication paths (buses, interfaces) before delving into component details.

- Transitioning to a Hierarchical Schematic: Each functional block in the Block Diagram becomes a lower-level schematic sub-sheet (or module), connected via Sheet Ports or hierarchical ports. This hierarchical structure not only improves readability but also adds significant value to the design in terms of modularity and testability. A clearly defined power block or RF front-end block can be reused across different projects. More importantly, testing efforts can be modularized: test plan creators can reference "Power Block Sheet 3" for initial testing, making the development of Functional Test (FT) procedures clearer and more precise.

3. Standards & Notation

Adherence to established drafting standards is mandatory in professional engineering documentation. Standards eliminate ambiguity, simplify collaboration across international teams, minimize manufacturing errors, and facilitate maintenance and reverse engineering.

3.1 Symbols and Reference Designators

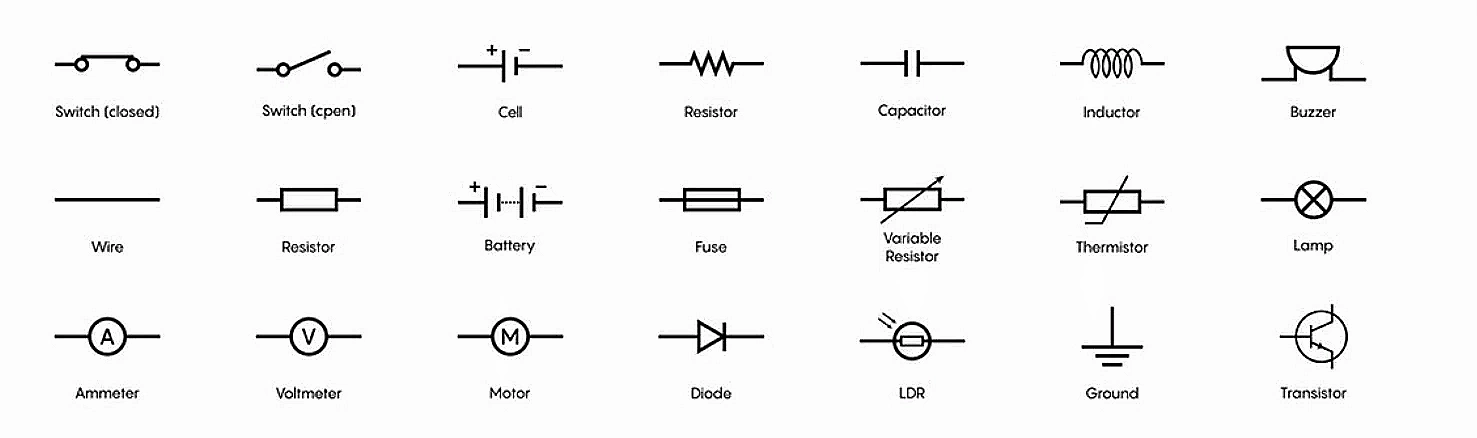

A Reference Designator (RefDes) is a unique identifier assigned to each component (e.g., R101, C22). Its letter prefix indicates the component type.

- Common Standards: The two most common standards define slightly different symbol styles (e.g., the European IEC resistor symbol versus the American IEEE resistor symbol).

- IEC 60617: The international standard, widely used globally, especially in Europe, covering a vast range of electrical and electronic components.

- IEEE/ANSI 315: Focuses on North American practices, defining graphic symbols and the standard RefDes system.

- Naming Rules: RefDes typically follows an alphabetical prefix followed by sequential numbers (e.g., C1, C2, C3). Numbering order often follows spatial layout (left-to-right, top-to-bottom) or functional grouping. Although ECAD tools can auto-handle sequential numbering, designers are advised to review this to ensure logical flow is clear.

When selecting RefDes letters, although standards exist (like IEEE 315), different companies or projects may have internal agreements. Internal company conventions take priority, maintaining consistency is paramount. For instance, frequency components should distinguish between passive crystals (Y) and active oscillator modules (X). The key is to ensure that within the entire design (including schematic and PCB Layout), each letter represents a unique component type to avoid ambiguity.

Table 2: Common Reference Designators (RefDes) Quick Reference

| RefDes |

Component Type |

Notes/Context |

| R |

Resistor |

Includes Variable Resistors (VR). |

| C |

Capacitor |

Includes polarized and non-polarized types. Polarized capacitors should use a curved plate symbol for distinction. |

| L |

Inductor |

Coils, chokes, ferrite beads (sometimes FB). |

| D |

Diode |

Includes LEDs. In the standard symbol, the bar side is the Cathode (K), and polarity must be clearly marked. LED symbols have "light arrows" pointing outward, and photodiode arrows pointing inward. |

| Q |

Transistor |

BJT, MOSFET, IGBT. |

| U |

Integrated Circuit (IC) |

Microcontrollers, op-amps, logic chips. |

| J / P |

Connector/Jack/Plug |

J is typically used for board-mounted connectors, P for plugs or mating components. |

| FB |

Ferrite Bead |

Specifically used to suppress high-frequency noise. |

| TP |

Test Point |

Critical for ICT and functional debugging. |

| Y |

Crystal / Resonator |

Passive frequency components. |

| X |

Oscillator Module |

Active frequency components. Some organizations also use U (IC) for clock chips. |

3.2 Title Block and Border Standards (Title Block / Border / Revision)

The Title Block transforms a simple drawing into a controlled engineering document, ensuring all stakeholders use the correct version with the right context.

- Standard Fields (Mandatory Data): Compliance with IEC 61082-1 (Electrical Documentation) and ASME Y14.100 / Y14.24 / Y14.35 (Engineering Drawing Practices, Drawing Types, and Revision Control) standardizes Title Block fields and revision processes; ASME Y14.1 is used for drawing sheet size and basic format. Key fields include:

- Title/Purpose: Description of the circuit (e.g., "Main Processor and Power Management").

- Drawing Number/Part Number (PN): Unique identifier for the drawing or project.

- Version and Revision: Current design iteration, critical for manufacturing synchronization.

- Date: Date of creation and last revision.

- Author/Checked/Approved: Chain of responsibility.

- Page Index: Current page number and total number of pages (e.g., Page 5 of 12).

- Company Information: Organization name, logo, etc.

Placement and Consistency: The Title Block is usually placed in the lower right-hand corner of the drawing for easy visibility. Maintaining consistent formatting across all drawings ensures easy recognition and interpretation, especially in multi-engineer collaborative projects.

3.3 Net Naming and Power/Ground

Clear and consistent Net Name conventions are the most important aspect of schematic readability and Netlist accuracy.

- Power Rails: Use clear prefixes and voltage values, typically all caps, to reflect the intended voltage and power domain. Naming should be highly consistent, for example: VCC_3V3 (for the 3.3V digital core), VBAT (for battery power).

- Differential Pairs: High-speed differential pairs must be identified with standardized suffixes to enable constraint management in the PCB Layout tool. Industry standards uniformly use _P and _N as suffixes, avoiding _POS or _NEG (e.g., USB_DP_P and USB_DP_N, or ETH_TX_P and ETH_TX_N).

- Buses and Grouping: Related signals should share the same prefix. Buses use square brackets to denote range (e.g., DATA[7..0]). Serial buses should be clearly named (e.g., I2C_SCL, I2C_SDA). Clock signals may explicitly indicate frequency (e.g., CLK_25M).

- Active-Low Signals: Signals that are active when logic low should be clearly marked, typically using a preceding slash (e.g., /RESET) or a suffix (e.g., RESET_L).

Net naming is no longer just annotation; for high-speed design, it is a constraint instruction.

For example, using the _P/_N naming convention for differential pairs enables the software to automatically group them as differential pair objects. This automatic grouping then allows the layout tools to apply complex physical rules like length matching and impedance control. This means the schematic designer defines the logical intent, which is translated into physical constraints via naming conventions. If there are typos or spaces in the net labels, the software will fail to recognize them as the same net, thereby breaking connectivity and preventing the transfer of critical layout rules.

Sidebar: Essential Schematic Standards Index

| Standard |

Area of Focus |

Key Control Domain |

| IEC 60617 |

International (Global) |

Graphical symbols and component representation for electro-technical diagrams |

| IEEE/ANSI 315 |

North American Practice |

Graphic symbols and standard RefDes system |

| IEC 61082-1 |

Documentation Practice |

Preparation and structuring of electrical documentation, including Title Block format, revision control, and connection representation. |

4. Reading a Schematic (Reading Methods)

Efficiently reading a schematic requires following a standardized, structured methodology, utilizing universally accepted signal flow conventions.

4.1 Starting with the Title Block and BOM

Before analyzing circuit connections, the document's context must first be established:

- Title Block First: Check the Title Block to understand the document's purpose, project part number, current revision, and total page count. This ensures the reader is using the latest and correct version.

- BOM/Component Overview: Scan the Bill of Materials (BOM) to understand the system's main components and complexity (e.g., "Is this a complex FPGA-based system, or a simple discrete component design?"). Knowing component types and values (e.g., R3 is 10k resistor) simplifies tracing.

Try NextPCB BOM Services

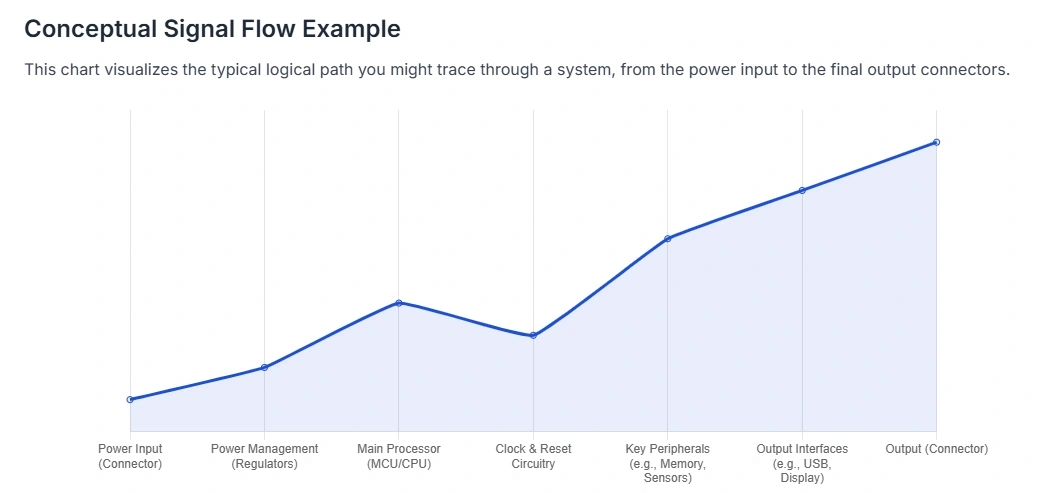

4.2 Signal Flow from Power to Load

A schematic should be laid out like a book, allowing signal flow to be tracked intuitively.

- General Signal Flow: Input signals typically enter from the left and flow toward the right, moving toward the output.

- Vertical Power Flow: DC voltage rails should be organized vertically. The highest positive potential is usually placed at the top, Ground (GND) at the bottom, and other voltage rails stacked in between. This visual hierarchy helps the reader quickly identify the Power Delivery Network (PDN).

- Identifying Functional Blocks: Good designers partition the circuit into logically independent, labeled functional blocks (e.g., "Clock Generator," "Microcontroller," "Interface Connectors"). When reading, first identify the power tree, primary clock sources, and system reset lines, as these are foundational to system operation.

4.3 Finding Key Nets and Test Points

Effective reading relies on using schematic labels to trace distributed signals, rather than solely depending on connection lines.

- The "Same Name, Same Net" Principle: Any connection tied to a visible Net Name (e.g., I2C_SDA) is electrically connected to every other point carrying that exact same label, regardless of physical distance or sheet separation. Designers widely use this principle instead of drawing long wires to reduce sheet clutter, especially for power and buses.

- Locating Test Points (TP): Test Points (RefDes TP) are explicit measurement locations, crucial for debugging and required for manufacturing tests like ICT. Identifying these points helps understand where signals can be easily accessed.

- Using RefDes for Communication: When discussing the circuit, components must always be referred to by their RefDes (e.g., "R3") rather than generic descriptions (e.g., "the third 10k resistor from the left") to ensure precision.

5. How to Create a Schematic (Practical Workflow)

Schematic design is a structured engineering process, not merely a drafting exercise. It culminates in generating the Netlist, the authoritative source of connectivity data.

5.1 Basic Workflow (General)

This general seven-step process is applicable to most professional ECAD environments, ensuring the shortest path from concept to deliverable:

New Project and Template Selection:

- Create a new project and select a standardized drawing template (A3/A4).

- Set Title Block information (PN, Rev).

- Define units and grid properties.

Component Placement and Footprint Mapping:

- Place schematic symbols onto the drawing.

- Crucially, verify that every symbol is linked to the correct physical PCB footprint (Footprint Mapping).

- Assign component values (e.g., 10k, 10uF).

Connecting Nets and Defining Net Classes:

- Draw connection lines between component pins. Ensure clear Junction Dots are used where three or more lines intersect.

- Assign descriptive Net Names to critical nets, power rails, and buses.

- Define Net Classes and Differential Pairs to enforce physical layout constraints on high-speed nets early in the design process.

Annotating RefDes and Net Name:

- Use the schematic editor's annotation tool to assign unique RefDes (R1, U5, C10) to all components, usually following functional or spatial order.

ERC (Electrical Rules Check) and Validation:

- Run the ERC tool to check for electrical and logical inconsistencies (e.g., output shorts, floating inputs, unconnected power pins, power net errors).

- Resolve all errors and critical warnings. This step validates connectivity against internal design rules.

Generate Netlist and Synchronize with PCB Project:

- Generate the Netlist, a text file containing all connectivity data (net names, RefDes, pin numbers).

- Import or synchronize this Netlist with the PCB Layout environment to begin the physical design.

Export Deliverables:

- Generate the final output package: PDF schematic, BOM, and Netlist.

5.2 KiCad Quick Guide

The KiCad user workflow is often streamlined:

- Startup and Library Management: Work within the Eeschema editor. Ensure symbol libraries and corresponding footprint library paths are correctly configured.

- Annotation and ERC: Run the "Annotate Schematic" tool to assign RefDes. The ERC tool must be run before proceeding to layout.

- Synchronization (Modern Flow): In recent versions of KiCad, the step of manually generating the .net file can often be skipped. Instead, use the "Update PCB from Schematic" function (often F8 or a dedicated icon), which handles annotation, Netlist generation, and import into Pcbnew (Layout editor) in one step. This ensures the correct transfer of component placement and footprint mapping.

5.3 Altium Quick Guide

- Altium Designer emphasizes high parameterization, unified data management, and hierarchical design capabilities:

- Templates and Parameterized Components: Utilize organized schematic templates that automatically populate Title Block information. Use parameterized components that directly link component data, simulation models, and footprints.

- Constraint Management via Directives: Place specialized directives (e.g., Parameter Set, Differential Pair Directive) directly on the schematic to define Net Classes and Differential Pairs. These directives define physical routing rules for high-speed nets before layout begins.

- Compilation and ECO: Run Project » Validate PCB Project to verify the unified data model. Use the Design » Update PCB Document (ECO) process to manage synchronization between the schematic and PCB Layout files, ensuring precise control over design changes.

The process of generating a Netlist in professional ECAD tools involves a compilation step that checks the "unified data model" for logical, electrical, and drafting errors. A robust Netlist is more than just a list of connections; it is the designer's assertion that the schematic fully adheres to the rules defined in the project settings.

6. Best Practices Checklist

A professional schematic is defined not only by its functionality but also by its readability, maintainability, and ability to preemptively flag layout and manufacturing issues.

- Consistent Net Naming: Ensure all power rails and ground nets use a single, consistent Net Name across all sheets (e.g., VCC_3V3, not VDD on one sheet and 3V3 on another).

- Connection Clarity: Connections at wire crossovers must be marked with clear Junction Dots. Wires crossing without a dot are not connected. To enhance clarity, avoid connecting more than three wires at a single point.

- Decoupling Capacitors (Power First Principle): Every power pin of every active IC must have an adjacent decoupling capacitor. These capacitors should be placed as close as possible to the IC pin and connected immediately to the ground plane.

- Handling Unused Pins: Explicitly terminate all unused inputs (especially CMOS logic) to prevent floating inputs and noise sensitivity. Clearly label all intentionally unconnected pins on ICs with an NC (No Connect) label.

- Signal Flow Direction: Maintain a consistent signal flow across all pages: left-to-right, top-to-bottom. Cross-sheet signal connectors should be placed on the extreme edges of the drawing (left side for inputs, right side for outputs).

- Organization and Annotation: Group related components into functional blocks and use borders or text boxes to define critical areas (e.g., power, clock, RF, interfaces). Add notes for critical design decisions (e.g., specific BOM notes, length matching tolerances required for Layout).

- Configuration Flexibility: Use 0-ohm series resistors to bridge configuration pins (mode pins, pull-up/pull-down) to GND/VCC. This provides flexible, non-destructive rework options during prototyping and debugging.

- Unit Standardization: Use standard unit prefixes for all component values. Avoid non-standard notation (e.g., 10K instead of 10k) to prevent ambiguity during BOM extraction.

Table 4: Standard Unit Prefixes

| Name |

Symbol |

Factor |

| Tera |

T |

10^12 |

| Giga |

G |

10^9 |

| Mega |

M |

10^6 |

| Kilo |

k |

10^3 |

| milli |

m |

10^-3 |

| micro |

µ |

10^-6 |

| nano |

n |

10^-9 |

| pico |

p |

10^-12 |

7. Common Mistakes (High-Frequency Errors)

Errors in schematic capture often lead to connectivity problems that bypass initial checks but cause catastrophic failures during prototyping or manufacturing.

| Error Type |

Description and Impact |

Mitigation Strategy |

| Missing Junction Dot |

Failure to place a clear dot at the intersection of three or more connection lines. Leads to misinterpretation: crossing lines may be incorrectly assumed to be connected or disconnected, corrupting the Netlist. |

Always use a junction dot for connections. To maintain clarity, avoid connecting four wires at a single point. |

| Inconsistent Net Naming |

Using different name variations for the same signal (e.g., VDD, 3V3, VDD_3V3). The ECAD tool treats them as three separate, unconnected nets (phantom connectivity failure). |

Enforce strict naming conventions (e.g., all caps, consistent delimiters). Run ERC to detect single-ended nets that should be connected. |

| Incorrect Polarity |

Placing polarized components (such as diodes, LEDs, tantalum, or electrolytic capacitors) in reverse orientation. The diode symbol's bar side is the Cathode (K) and must connect to the lower potential. The positive lead of the capacitor must face the higher voltage. Check the schematic symbol markings (cathode bar, curved plate) for indication. |

|

| Missing Power Source |

VCC/GND pins on an IC are drawn but not explicitly connected to a designated power port/Net Name. This type of oversight is one of the most common high-risk error types. |

Use dedicated, visible power port symbols (e.g., VCC_3V3, GND) for power nets, and thoroughly enable power net integrity checks in the ERC. |

| Missing Constraint Notes |

Failure to add annotations or directives for high-speed nets requiring specific Layout rules (e.g., "Differential Pair: 100-ohm impedance, requires length matching"). |

Use schematic directives or detailed text annotations on relevant nets/buses to guide the layout engineer. |

8. From Schematic to Manufacturing (Production Realization)

The final output of the schematic is the Design Package, which is the core medium of communication with the PCB manufacturer, assembly house, and test engineering team.

8.1 Deliverables Package (Design Package)

The complete manufacturing package is directly derived from the verified schematic and ECAD project structure.

- Schematic Files (PDF/Source Files): The high-resolution PDF version of the final, annotated, and ERC-verified schematic (for viewing), along with potential native source files (e.g., .SchDoc, .kicad_sch) for Layout verification.

- Bill of Materials (BOM): The authoritative list of all components, linked to the RefDes in the schematic. A professional BOM must include part numbers, manufacturers, descriptions, quantities, and critical fields for alternative or substitute parts.

- Netlist: This is the most crucial digital deliverable, mapping component pins to Net Names.

- IPC-D-356: The preferred ASCII Netlist format, specifically used for bare board testing and DFM verification.

- ODB++: A unified file format that includes Netlist data alongside Gerbers and layer stackup, considered the preferred choice for high-reliability manufacturing.

Manufacturers use Gerber files (physical copper layer data) for fabrication, but they use the Netlist (logical connectivity data) to verify the Gerbers' correctness. If a trace opens or shorts unexpectedly in the Layout but is not visibly obvious in the Gerber files, the IPC-D-356 Netlist check will flag the discrepancy during DFM verification. Thus, the Netlist generated from the schematic acts as the authoritative, "legal" definition of required connectivity. It is the core input for DFM compliance checks and bare board test fixture programming.

> Recommend reading: Scheme-It: An Online Schematic and Diagramming Tool

Try Open Source Online Gerber Viewer from NextPCB

8.2 Interfacing with DFM/Testing

The schematic designer must embed testing and manufacturing requirements into the logical design.

- DFM Constraints from Schematic: High-speed nets defined as Differential Pairs or Net Classes in the schematic directly pass physical design rules (trace width, spacing, length matching) to the layout engineer. Additionally, schematic annotations can indicate critical component height limits or sensitive component grouping.

- Testability (ICT Points): The schematic must proactively include Test Points (RefDes TP) on all critical nets (power, clocks, major buses) to ensure the board is testable. This information is used to build the "bed-of-nails" fixture required for In-Circuit Testing (ICT). ICT checks components and shorts/opens based on the Netlist definition from the schematic.

- Functional Test (FT) Support: Logical partitioning (see section 2.2) and critical net labels (see section 3.3) in the schematic directly assist test engineers in writing functional test code and programs, linking software tests to physical pins and components.

9. FAQ

| Question |

Answer |

| What is the core difference between a Schematic Diagram and a Wiring Diagram? |

A schematic displays electrical connections logically, focusing on function and clarity, not physical location. A Wiring Diagram shows the physical routing of wires and components for assembly purposes. |

| What standards must a schematic follow? |

Schematics should primarily follow IEC 60617 (international symbols) or IEEE/ANSI 315 (North American symbols and RefDes), ensuring the symbols and documentation are universally understood. |

| How should the title block be set up? |

The Title Block must contain comprehensive project metadata: drawing title, unique drawing number (PN), version/revision, date, and author/approval signatures, typically adhering to standards like IEC 61082-1. |

| What files should be delivered after the schematic is complete? |

Core manufacturing deliverables include the final schematic PDF, the Bill of Materials (BOM), and the authoritative Netlist (preferably IPC-D-356 or contained within ODB++). |

| What tools/plugins can automatically check for errors? |

The most critical automated check is the Electrical Rules Check (ERC), available in all professional ECAD tools (like Altium, KiCad). ERC identifies connectivity and power net anomalies before the Netlist is generated. |

10. Glossary (Quick Reference)

| Term |

Definition |

| Schematic Diagram |

A logical representation of a circuit using abstract symbols to define electrical connections (nets). |

| Wiring Diagram |

A drawing that shows the physical point-to-point connections used for assembly or harness creation. |

| PCB Layout |

The physical design file defining the placement of components, layer stackup, and copper routing on a Printed Circuit Board. |

| Net |

An electrical node or connection path between two or more component pins, identified by a unique net label. |

| RefDes (Reference Designator) |

The unique alphanumeric identifier assigned to each component in the schematic (e.g., R5, U1). |

| ERC (Electrical Rules Check) |

An automated validation tool run on the schematic to ensure logical and electrical integrity. |

| Netlist |

A text file derived from the schematic that lists all electrical connections (nets, pins, and RefDes), serving as the core input for PCB Layout and manufacturing testing. |

| Title Block |

The standardized data block on an engineering drawing that contains necessary document control information (revision, date, title, part number). |

| BOM (Bill of Materials) |

The authoritative list of all components required for assembly, derived from the schematic component definitions. |

| Diff Pair (Differential Pair) |

Two tightly coupled nets (labeled _P and _N) carrying complementary signals, constrained in the schematic to meet specific impedance and length requirements in the Layout. |

About the Author

Sylvia joined NextPCB two years ago and has already become the go-to partner for clients who need more than just boards. By orchestrating supply-chain resources and refining every step from prototype to mass production, she has repeatedly delivered measurable cost savings and zero-defect launches. Consistency is her hallmark: every client, every order, receives the same uncompromising quality and responsive service.