PCBs made with high glass transition temperature (Tg) materials, typically 170°C and above.

- Enhanced thermal resistance and stability

- Improved mechanical strength at high temperatures

- Reduced thermal expansion

- Better chemical resistance

Support Team

Feedback:

support@nextpcb.comTable of Contents

Key Insights:

- Mastering the Fundamentals: Clearly distinguish between High-Speed Design (focusing on signal transition speed and clock alignment) and High-Frequency Design (focusing on wavelength and energy loss).

- Material Selection Logic: A look at the trade-off between cost and Dissipation Factor (Df) for high-speed boards versus the strict requirement for Dielectric Constant (Dk) stability in high-frequency boards.

- Design Strategy Comparison: A breakdown of "Length Matching & Timing" tactics for high-speed routing versus the "Shortest Path & Impedance Matching" rules for high-frequency routing.

- Practical Pro Tips: Real-world solutions including Hybrid Stackups for cost reduction, specialized via handling, reverse-treated foil (RTF), and validation methods like Eye Diagrams and S-parameters.

In the early stages of PCB design, many engineers fall into a common trap: assuming that if a board has a high frequency, it’s a "High-Frequency" board, and if it runs fast, it’s a "High-Speed" board. While they sound similar, choosing the wrong design path based on this intuition can lead to costly failures.

In essence, High-Speed PCB design is a race against time. It focuses on the time-domain performance of digital signals—ensuring that billions of 0s and 1s flip precisely at the right nanosecond without getting garbled. We focus on rise/fall times, setup times, and hold times.

In contrast, High-Frequency PCB design is a battle against energy loss. It focuses on the frequency-domain purity of analog or RF signals—ensuring that weak signals travel through the board with minimal attenuation or interference. Here, wavelength, power, and phase are the stars of the show.

Understanding this fundamental split is the first step toward making the right calls in material selection and routing strategy.

When talking about high-speed circuits, the clock frequency (MHz or GHz) can be a misleading metric. What truly defines a circuit as "high-speed" is the Rise Time (Tr) of the signal.

Imagine a 50MHz clock signal with a very sharp 1ns rise time. According to Fourier analysis, this signal contains extremely rich high-frequency harmonic components. If the PCB isn't designed to handle these harmonics, the edges will round off, turning a clean square wave into something resembling a sine wave, eventually leading to data errors.

In high-speed designs (like DDR5 or PCIe 6.0), engineers spend most of their energy on Signal Integrity (SI). This means tackling reflections caused by impedance diconnects, crosstalk between traces, and ground bounce from messy reference planes.

For high-frequency circuits (typically RF/Microwave circuits above 1GHz), the signal is no longer just a voltage level; it’s an electromagnetic wave propagating along a transmission line.

At these frequencies, Skin Effect and Dielectric Loss become the primary enemies. Current no longer flows through the whole conductor but crowds onto a thin layer at the surface. Meanwhile, the PCB material itself "soaks up" some of the signal's energy and turns it into heat.

The goal here is fidelity. Whether it’s a 5G base station or an automotive millimeter-wave radar, the designer is fighting to maintain power levels and phase characteristics while avoiding Passive Intermodulation (PIM).

| Feature | High-Speed PCB | High-Frequency PCB |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Type | Digital Square Wave (Timing) | Analog Sine/Modulated Wave (Energy) |

| Key Challenge | Reflections, Crosstalk, Jitter | Insertion Loss, Phase Noise, VSWR |

| Impedance | Focus on Differential pair & Common-mode | Focus on absolute 50Ω/75Ω accuracy |

| Routing Mantra | Match lengths, Use serpentine traces | Keep it short, Keep it simple, Avoid vias |

| Sensitivity | Sensitive to Via-induced discontinuities | Sensitive to Copper roughness & Corner effects |

The substrate determines the performance ceiling of your product. There are two "magic numbers" you need to know: the Dielectric Constant (Dk) and the Dissipation Factor (Df).

>> See Deatailed High-Speed Material List

For high-speed digital circuits, the priority is preventing the medium from "filtering out" the signal's harmonics. The lower the Df value, the less the signal rounds off.

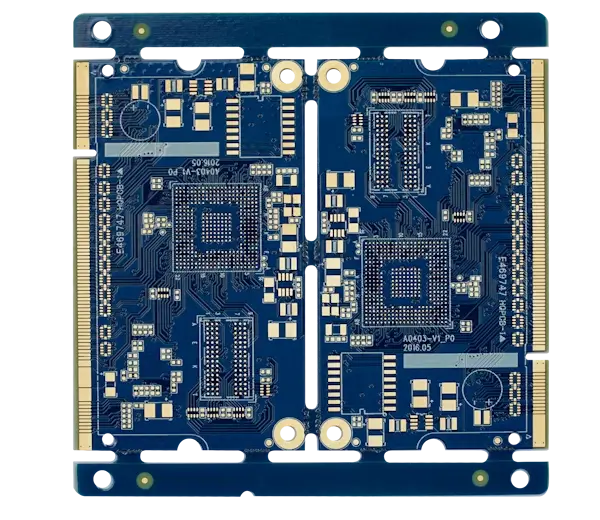

However, high-speed boards are often large and multi-layered (like server motherboards), making them very cost-sensitive. Engineers usually skip expensive PTFE and opt for Enhanced FR-4 or Low-loss Resins (e.g., Panasonic Megtron series or Isola Tachyon). These offer a great Df (between 0.002 and 0.005) while remaining easy to manufacture.

>> Material Selection for High-Frequency PCBs

In RF design, Dk stability is everything. A tiny shift in Dk changes the impedance of your line, causing reflections or shifting the center frequency of a filter.

This is why high-frequency boards often use PTFE (Teflon) or Ceramic-filled Hydrocarbons (like Rogers RO4000 series).

Pro Tip: In complex systems like 5G base stations, we often use Hybrid Stackups. We use expensive Rogers material on the top layers for RF signals and cheap FR-4 for the internal power and control layers. It’s like putting a racing engine in a standard chassis—all the speed, half the cost.

High-speed routing is like conducting a marching band. Every bit of data must arrive at the destination exactly in sync with the clock.

High-frequency routing follows a "less is more" philosophy. Every millimeter of wire and every via adds parasitic inductance and capacitance—which is pure poison for microwaves.

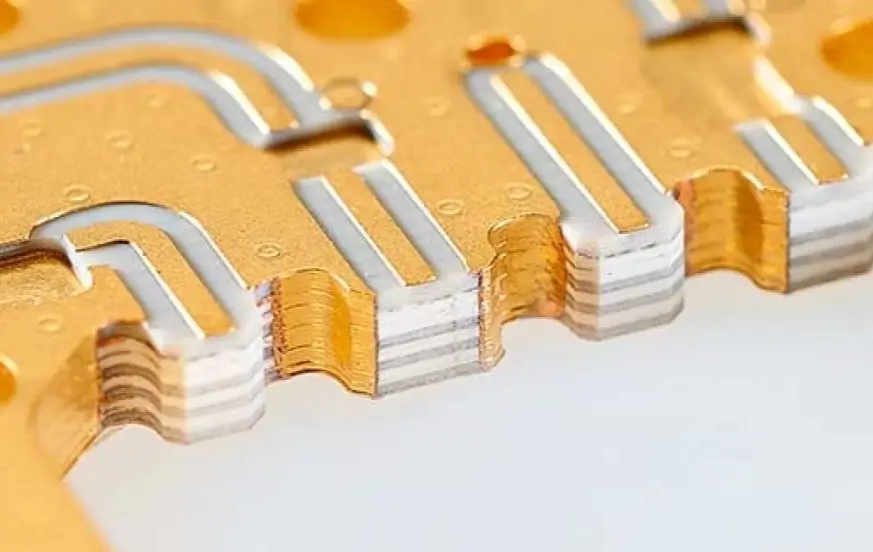

High-speed boards care about Impedance Control (usually ±10%). High-frequency boards, however, push the limits of physics. For 77GHz radar, line width tolerances must be within ±0.02mm. Even the "bumpiness" of the copper (Surface Roughness) matters—smooth signals need smooth copper, so we use Reverse Treated Foil (RTF) or HVLP copper.

When it’s time for "the physical":

A PCB is considered “highspeed” when the signal rise/fall times and edge rates are fast enough that simple wiring assumptions break down and transmission line effects dominate. This means that impedance control, reflections, crosstalk, and timing skew all need to be managed during layout and stackup design. It’s not just about clock frequency — it’s about how fast the signal transitions relative to the trace length.

Although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they have different design goals.

Material choices differ because of the design priorities:

The layout emphasis differs:

Different validation approaches are used:

High-speed and high-frequency design might share the same physics, but their methodologies are worlds apart. One is a race for logical certainty in a tiny window of time; the other is a quest for energy purity over a long distance.

A great PCB engineer knows how to calculate impedance—but a master knows how to find the sweet spot between cost, manufacturability, and performance.

This guide is based on IPC standards and industry best practices. Always validate your specific design with simulation and manufacturer feedback.

>>IPC-A-610 >>IPC-A-600 >>IPC 6012 >>IPC-2221

Optimize Your Design & Accelerate Production

Upload & Get Professional DFM Review Today Get Advanced PCB Capabilities at NextPCB

Still, need help? Contact Us: support@nextpcb.com

Need a PCB or PCBA quote? Quote now