Stacy Lu

Support Team

Feedback:

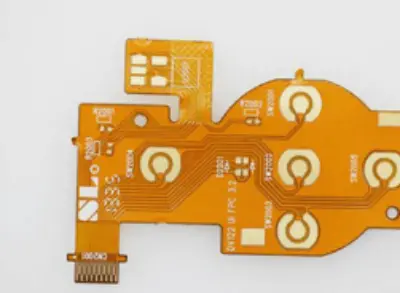

support@nextpcb.comFlexible Printed Circuit Boards (Flex PCBs) have revolutionized modern electronics, enabling designs that fold, twist, and fit into ultra-compact, non-planar spaces—from high-end wrist wearables to critical automotive sensors. However, transitioning from rigid boards to flexible circuits requires a shift in mindset. Designing a board that moves is fundamentally different from designing a rigid FR4 board that stays static.

If you are still in the early stages of deciding which board type fits your project, check our comprehensive comparison: Flex vs. Rigid vs. Rigid-Flex PCBs: Which One Do You Need?

For those ready to start designing, this guide dives deep into the critical materials, mechanical layout rules, and cost factors you need to master to ensure your flex circuit is not only manufacturable but also reliable over its lifespan.

Unlike traditional rigid boards that rely on fiberglass-reinforced epoxy (FR4) for structure, Flex PCBs utilize flexible polymers as the base substrate. This fundamental difference allows the circuit to conform to specific housing shapes or endure repeated dynamic flexing during operation. While this offers incredible versatility, it introduces new challenges regarding mechanical stress, tear resistance, and thermal management that every engineer must address.

Selecting the right material is the first and most critical step in flex design. Your choice will dictate the board's flexibility, thermal resistance, and overall cost. Unlike rigid boards where FR4 is the default, flex boards require you to balance mechanical properties with electrical performance.

To help you make an informed decision, here is a comparison of the most common substrate materials:

| Material | Key Characteristics | Thermal Resistance | Cost | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyimide (Kapton) | Excellent flexibility, chemical resistance, and thermal stability. The industry standard. | High (Compatible with reflow soldering) | Medium-High | Industrial, Medical, Automotive, Aerospace |

| Polyester (PET) | Good flexibility and electrical properties but melts at high temps. Cannot be reflow soldered. | Low | Low | Membrane switches, low-cost consumer toys |

| LCP (Liquid Crystal Polymer) | Superior high-frequency performance with low moisture absorption. | High | Very High | 5G antennas, High-speed data transmission |

Expert Tip: For most generic flex circuits requiring component assembly, Polyimide offers the best trade-off between performance, manufacturability, and cost.

Designing for flex requires a "mechanical mindset." The copper on a flex board is thin and ductile, but it behaves differently under stress than on a rigid board. Ignoring these mechanical constraints is the leading cause of field failures.

Copper will crack if bent too sharply. To prevent this, you must adhere to minimum bend radius standards based on the board's thickness and usage profile.

| Flex Type | Definition | Recommended Minimum Bend Radius |

|---|---|---|

| Static Flex (Install-to-Fit) | The board is bent once during installation and remains fixed. | 6x - 10x the board thickness |

| Dynamic Flex | The board is continuously flexing during operation (e.g., a printer head cable). | 12x - 20x the board thickness |

Mechanical stress management is key to preventing trace fractures:

Flex substrates bond less aggressively with copper than rigid FR4. This means pads can easily peel off (delaminate) if pulled or heated too much.

A common misconception is that a flex board must be flexible everywhere. In reality, most flex boards are "hybrid" structures. Stiffeners are non-conductive mechanical supports added to specific areas of the flex circuit to provide a stable base.

Engineers are often surprised to find that Flex PCBs can cost 2-3x more than rigid PCBs at low volumes. Understanding the "why" behind this cost can help you design more economically.

Based on NextPCB’s 15 years of manufacturing experience, avoiding these common pitfalls can save you costly respins:

Designing a flex board involves a delicate balance between electrical performance and mechanical endurance. While the process is more complex than rigid PCB design, the ability to fit electronics into any shape provides a powerful competitive advantage for your product.

Need Speed? Accelerate with NextPCB’s Quick Turn Services

Time-to-market is critical. For engineers who need to validate designs fast, NextPCB offers a dedicated Quick Turn PCB Prototyping service tailored for flex circuits. We bridge the gap between design and physical product with speed and precision:

Don't let fabrication challenges slow down your innovation.

Get an Instant Quote for Flex PCB Assembly Engineer Consultation

Flexible PCB design requires planning for mechanical bending as well as electrical routing. Start with defining your stack‑up, materials (such as polyimide), and expected bend regions. Ensure the bend radius and layer structure accommodates both electrical and mechanical requirements. Since flex areas are prone to stress, avoid placing vias and heavy components near these zones and route traces with smooth, gradual curves to minimize stress.:contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

Copper traces in bending areas experience tensile and compressive stresses that can cause cracking, delamination, or open circuits if the bend radius is too small or routing is improper. Use minimum bend radius rules (e.g., 10× board thickness for dynamic bends) and route traces perpendicular to the bend axis to distribute stress evenly. Avoid right‑angle turns and sharp trace corners inside flex zones.:contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}

The bend radius is the smallest radius at which a flex PCB can bend without damage. It depends on total board thickness and layer count. A general guideline is at least 6–10× thickness for static bends and 100× thickness for dynamic bends. Ensuring sufficient bend radius helps prevent trace fractures, layer delamination, and fatigue failures in repeated use.:contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

Sharp trace corners, trace stacking in bend areas, and placing vias/pads inside flex zones are frequent pitfalls. Traces routed improperly concentrate stress and can rapidly lead to fractures during bending. Follow guidelines such as using curved or perpendicular routing relative to bend axes, maintaining uniform trace width in flex regions, and keeping holes away from stress zones to improve durability.:contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}

Yes. Components, heavy pads, and vias in bend zones significantly increase the risk of mechanical stress failures. Vias introduce rigid points that do not bend with the flex, leading to cracking or delamination. Keep these features outside of bend regions and use teardrop reinforcements or stiffeners where needed to support traces and pads near high‑stress areas.:contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}

Still, need help? Contact Us: support@nextpcb.com

Need a PCB or PCBA quote? Quote now